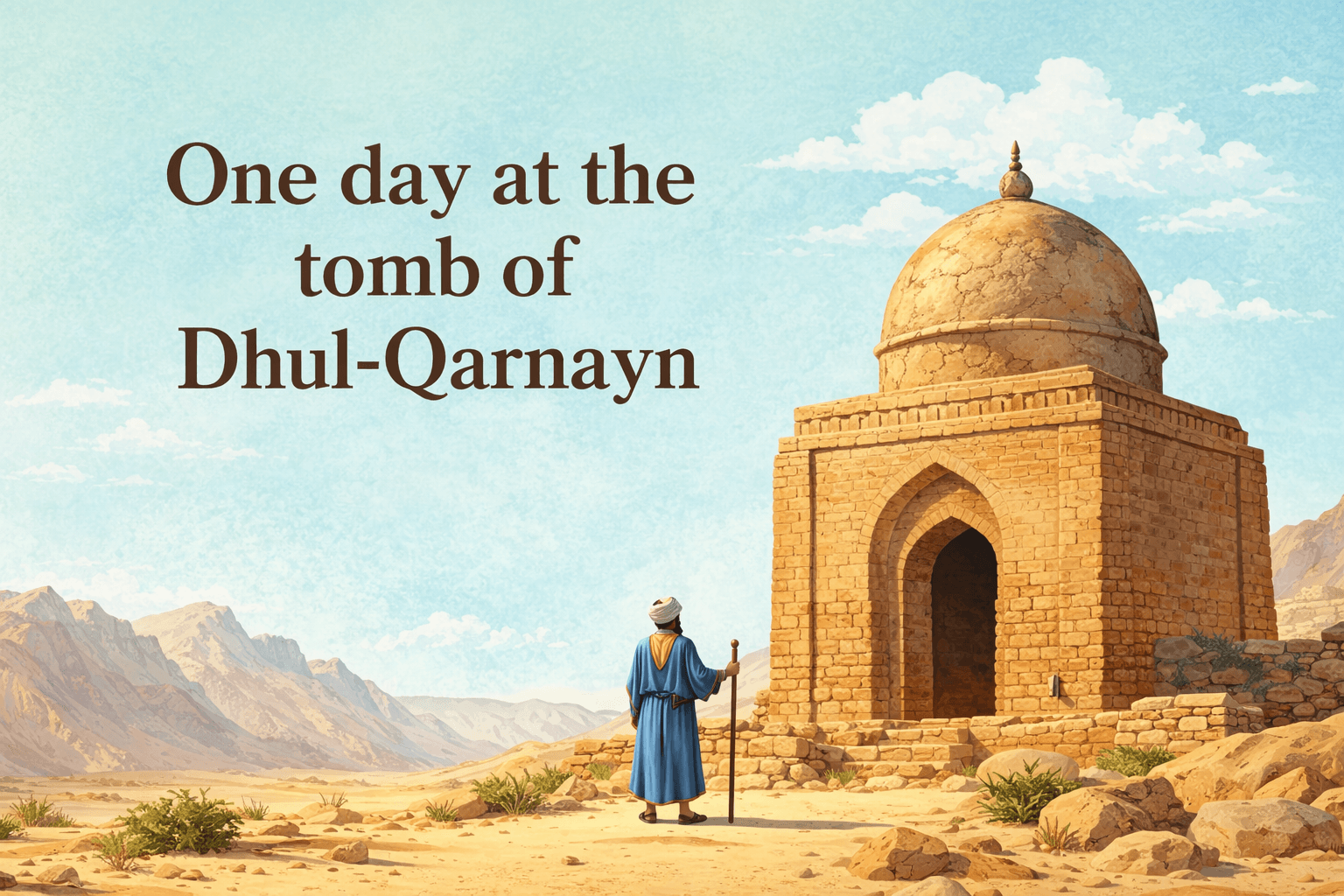

Behind the vast open plain stood towering mountains, their peaks covered with fresh snow. Icy winds sliced through the air, cutting through our jackets and scarves, making it difficult to remain standing. The cold of late December pierced our lungs as twenty-two of us struggled against the freezing gusts. Before us stood the tomb of a man whom Allah Almighty mentions with profound respect in the Holy Qur’an. To Muslims, he is known as Dhul-Qarnayn; to the Greeks, Cyrus; and to Iranians, Kourosh the Great.

The tomb stood alone in an expansive field stretching endlessly in all directions, framed by snow-capped mountains at the horizon. In that hauntingly beautiful yet unforgiving landscape, history seemed to breathe alongside us.

Birth and Early Life of Cyrus the Great

Cyrus was the first great king of Iran—also known historically as Persia. He was born in 600 BC in Anshan, an ancient city now identified as Tall-e Malyan, located in the Zagros Mountains, about 46 kilometres from Shiraz. His father was Cambyses I, and his mother, Mandane, was the daughter of the Median king.

Before Cyrus was born, his grandfather saw a troubling dream in which a great flood emerged from his daughter’s womb, followed by vast orchards spreading across the land. The royal astrologers interpreted this as a sign that a future ruler—one who would overthrow him—was growing in Mandane’s womb. Fearing the loss of power, the king ordered his trusted general, Harpagus, to kill the child at birth.

However, when Cyrus was born, Harpagus could not bring himself to murder the innocent infant. Instead, he secretly handed the baby to a shepherd, sparing his life. Raised among shepherds and farmers, Cyrus grew up far from royal courts, yet his bearing, confidence, and authority marked him as extraordinary. Even as a boy, he naturally commanded others and punished disobedience with a king-like authority.

Years later, after the death of his grandfather and the rise of a new ruler, Cyrus’ mother learned that her son was alive. She searched tirelessly until she found him. Though raised as a shepherd, Cyrus carried himself like royalty. Eventually, he was brought to the palace, where destiny awaited him.

Meanwhile, Harpagus suffered a horrific punishment at the hands of the former king, who ordered Harpagus’ own son to be slaughtered and served to him as a meal. This cruelty turned Harpagus against the throne, and he later played a crucial role in helping Cyrus rise to power.

Rise of the First World Empire

After years of warfare, Cyrus seized power in 559 BC. Allah Almighty granted him authority on earth, and he did not confine himself to a small kingdom. He expanded relentlessly, first conquering Media, a powerful empire stretching from Mesopotamia to present-day Hamadan. Then came Lydia (modern-day Turkey), followed by Babylon (Iraq), Egypt, Nubia, and Libya.

His empire stretched from Central Asia to Europe, and from the Caspian Sea to the Indus Valley, making Balochistan a part of his realm. Cyrus became the first ruler in history to govern such an extensive territory, earning his place as the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the greatest superpower of the ancient world.

The name Cyrus signifies “one who shines like the sun,” a meaning reflected in his legacy.

Champion of Justice and Humanity

Despite his vast power, Cyrus ruled with compassion and justice. Having grown up among poor farmers and shepherds, he understood the suffering of ordinary people. He remembered the pain of his mother and rejected male dominance, advocating equality between men and women. He opposed religious persecution, declaring that religion should unite humanity, not divide it through bloodshed.

Cyrus was also firmly against slavery. To formalise these beliefs, he introduced the world’s first Charter of Human Rights, inscribed on a clay cylinder and placed in Babylon. This historic document proclaimed religious freedom, equality, and justice for all. Today, the Cyrus Cylinder is preserved in the British Museum, with a replica displayed at the United Nations Headquarters in New York.

Journey to the Ends of the Earth

Cyrus later pursued two profound ambitions: to discover the Water of Life and to reach the places where the sun rises and sets. Upon reaching the spring of immortality, he witnessed creatures that were ancient, deformed, and miserable—unable to die despite unbearable suffering. Disturbed by this sight, he abandoned the quest for immortality.

Historians and religious scholars agree that Cyrus successfully journeyed to the far east and west—likely reaching the Indian Ocean and the Caspian Sea. Allah Almighty mentions him with honour in Surah Al-Kahf, stating:

“Indeed, We established him upon the earth and gave him a way to everything.”

The Qur’an also narrates his encounter with peoples at the place of sunset and his construction of a massive barrier against Gog and Magog.

The Wall of Gorgan

To protect the people of Gorgan from northern invaders, Cyrus built a 195-kilometre-long fortified wall along the Caspian Sea, complete with 30 strong forts. Known as the Wall of Gorgan or Sadd-e-Iskandari, it still stands today as a testament to his engineering genius.

Protector of Religions

Cyrus showed exceptional kindness to the Jews. After conquering Babylon in 539 BC, he freed Jewish captives enslaved by Nebuchadnezzar and allowed them to return to Palestine to remember and rebuild the Temple of Solomon. He also permitted Jews to settle in Iran. For this, he is honoured as the only non-Jew praised in the Bible, particularly in the Book of Isaiah.

He also supported fire worshippers, spreading Zoroastrian beliefs as far as China, and introduced administrative systems that shaped governance for centuries. He divided his empire into provinces, founded the world’s first bureaucracy, and built the Royal Road, the first intercontinental highway.

Death and Legacy

Cyrus ruled for 29 years before dying in 530 BC. He had his tomb constructed during his lifetime at Pasargadae, near his palace. The structure, carved from massive stone blocks, stood majestically amid gardens—so beautiful that the Greeks named the region Pasargadae, meaning Persian Gardens.

In 330 BC, Alexander the Great destroyed the city but spared Cyrus’ tomb. Inside, inscriptions read:

“I am Cyrus the Great, who founded the Persian Empire. O man, do not begrudge me this small piece of earth that covers my bones.”

The historian Herodotus confirmed that Cyrus remains buried there to this day.

A Journey Through Time

I reached Pasargadae on December 30, 2025, after a three-hour journey from Isfahan along the Isfahan–Shiraz road. Leaving the highway, a straight government-built road led us directly to the tomb. Like the pyramids of Giza, it captured our gaze instantly. We stood silently before it, overwhelmed—breathing history, standing where greatness once walked.